Have you ever wondered what happens when your personal information is stolen? Think about it, you see or hear news about a major data breach, where usernames and passwords have been compromised, but what does that mean exactly? After a recent incident, I thought perhaps a blog on the topic might be useful to those of you who don’t follow the actions of criminals on a granular level.

The Backstory

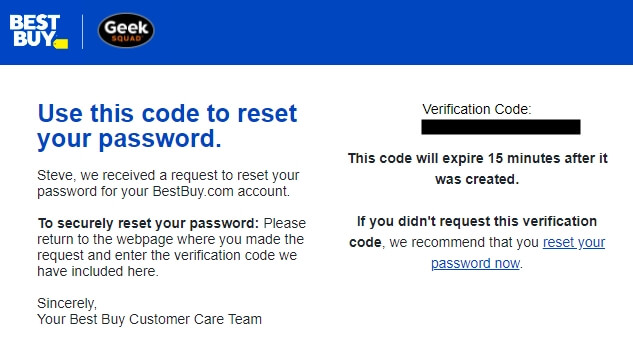

I was watching TV not too long ago (January 16) when I got a rather odd email from BestBuy, a big-box tech retailer here in the United States. It was a password reset notification, and the email had the one-time password (OTP) needed to complete the reset process. The thing is, I never requested a reset. In fact, while I do have a BestBuy account, I rarely use it outside of holiday shopping once a year.

That was an odd thing to see, and it would be alarming if my BestBuy account was critical.

But it got me thinking, and I recalled that my personal details were involved in the recent Twitter leak. This leak included various bits of information about myself, including my email address. I know the Twitter data has been circulating in various places online. So I sort of expected something to happen eventually.

My BestBuy account isn’t important. At least not in the grand scheme of things.

It’s handy when I do birthday shopping or Christmas shopping, but that’s about it. At this point, I figured it was a criminal running a verification check, and decided to lock the account down fully. This involved registering the account with my password manager (changing the password to something that is random, as well as lengthy) and enabling multi-factor authentication (MFA).

What Happens to Your Data Once it is Stolen

As I said, I figured the criminal was running verifications.

During a basic verification check, a criminal handling compromised usernames and passwords will simply check to see if the targeted account exists. What they’ll do is run though a list of services or accounts (shopping, social media, banking, etc.), and verify the target account by checking password reset functions. After that, they’ll circle back later and attempt an ATO or account takeover. These checks are usually part of a credential stuffing attack1.

It is possible the criminal already had a list of passwords associated with my email address, and initiated a password reset once the items on their list failed. However, because this only happened once, I think it was just a confirmation check.

It’s certain the criminal now knows I have a BestBuy account. Yet, because I locked it down with all of the security features available to me, I’m confident this knowledge is worthless to them.

Combo Lists and Password Lists

Once a criminal has verified the accounts related to a given set of credentials, and in some cases confirmed the logins are valid, they need to process and unload these newly minted account lists. The method of doing this is a bit of a hodgepodge of actions and activities. It isn’t a consistent process by any means.

Sometimes the account lists are sold off or traded immediately, and usually to groups who then do the actual ATO work. If these lists include corporate access, those accounts are parceled off and sold or traded to access brokers, who then sell the lists to ransomware affiliates. These affiliates are the ones who will then undertake the work of trying to infect the company.

Now I say lists, as in multiples, but this process is the same for single accounts as well. If it seems confusing, it is. It can be hard to keep up on this stuff, and researchers spend hours connecting the dots and trying to track criminals and their trade.

Once the lists have been sorted and offered up to the top-level criminals, it’s time to move what’s left, or what has been aged out 2. These leftovers will often find their way down to the public criminal market.

Consumer Targeting in the Public Criminal Market

When it comes to public criminal markets, we’re going to stick to looking at consumer victims, and skip the corporate side of things where ransomware affiliates and access brokers live. So we’re just going to look at the mid-level, or low-level credential brokers. The ones who promise fresh accounts, and specialize in various accounts and services.

Credential brokers will take their collections sort them out by account, age, location, and other details. For example, it is possible to find combination lists for people in Germany who use Telekom or Vodafone, and whose email accounts have been compromised. Once in a while you’ll see criminals maintain their access and age the accounts. Aged accounts are useful, because they are often exempt from various security checks and purchase or access limitations.

There are combination lists available for specific ISPs, email providers, hosting providers, retailers (Target, Walmart, BestBuy, HomeDepot, Lowes, Kroger, Costco), services (PayPal, Spotify, Netflix, Hulu, HBO, Disney+, DoorDash, Uber Eats), gaming, etc.

Just about anything you can think of, criminals will create it, market it, and sell or trade it.

The prices are constantly in flux. Some accounts sell for as little as a single dollar, while others can go for $50 or more, depending on the asset and it’s connected variables. For example, a Walmart account with a credit card associated with it is worth more than a general Walmart account. An aged Walmart account could be worth more than either of them.

Like any market, something is only worth what someone else is willing to pay for it. Sometimes, criminals will create accounts using a person’s compromised personal details, and they’ll sell those off too. So if you didn’t have a Crunchyroll account before, you do now.

The following links show examples of accounts being sold online for BestBuy, Walmart, Target, and Home Depot

So What Can You Do About This?

Your data is online. That can be a scary thought, but if you accept that, life gets easier. There have been so many data breaches and leaks that it seems impossible to keep everything private. However, you do have some control, should you choose to exercise it.

-

Password Managers: You should be using a password manager for everything that is critical and important. At the very least, use one for your financial accounts, email accounts, social media, and sensitive accounts such as medical accounts.

-

Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA): You should be using this as well, everywhere it is available. Try and avoid SMS-based MFA, but if that is all you have, then use it. Google Authenticator and Duo are the most common authenticators, but 1Password (password manager) also has them embedded, and can manage that for you as well.

-

Statements and Credit History: Watch your bank statements and your credit history. Dispute anything that seems off, the moment you see it.

Using these three things together will make it much harder for criminals to take over your accounts, run up random charges, or open random credit-based accounts. Not to mention, because your password manager will generate secure, completely random passwords any that have previously leaked will be useless once you go though the process of changing things out.

-

Credential stuffing attacks are where a criminal has a username and password, and then attempts to use this combination of credentials across several websites and services. For example, if they had a valid email login

(user@gmail.com:password)they would attempt to use this combination on social media platforms, various online services such as Spotify, and retailers, like BestBuy, Walmart, or Target. These attacks are usually automated, and the criminal will run a list of hundreds, sometimes thousands of passwords against a given platform or service. ↩ -

By aged out, I mean a collection of usernames and passwords that is old (30-days or more) and has little or no use to ransomware affiliates, or other bulk buyers. ↩