I know. It’s been almost a year since I last blogged anything.

Truth is, I got busy, and I just didn’t have the drive to write. Also, there wasn’t much to write about. My AI experiment worked, but then changes to OpenAI broke everything. Truth be told, I’m wondering if I should cancel my OpenAI subscription. I don’t use it all that much.

It was just a long, really rough year. But something happened today that gave me a bit of a spark, so here I am writing about it.

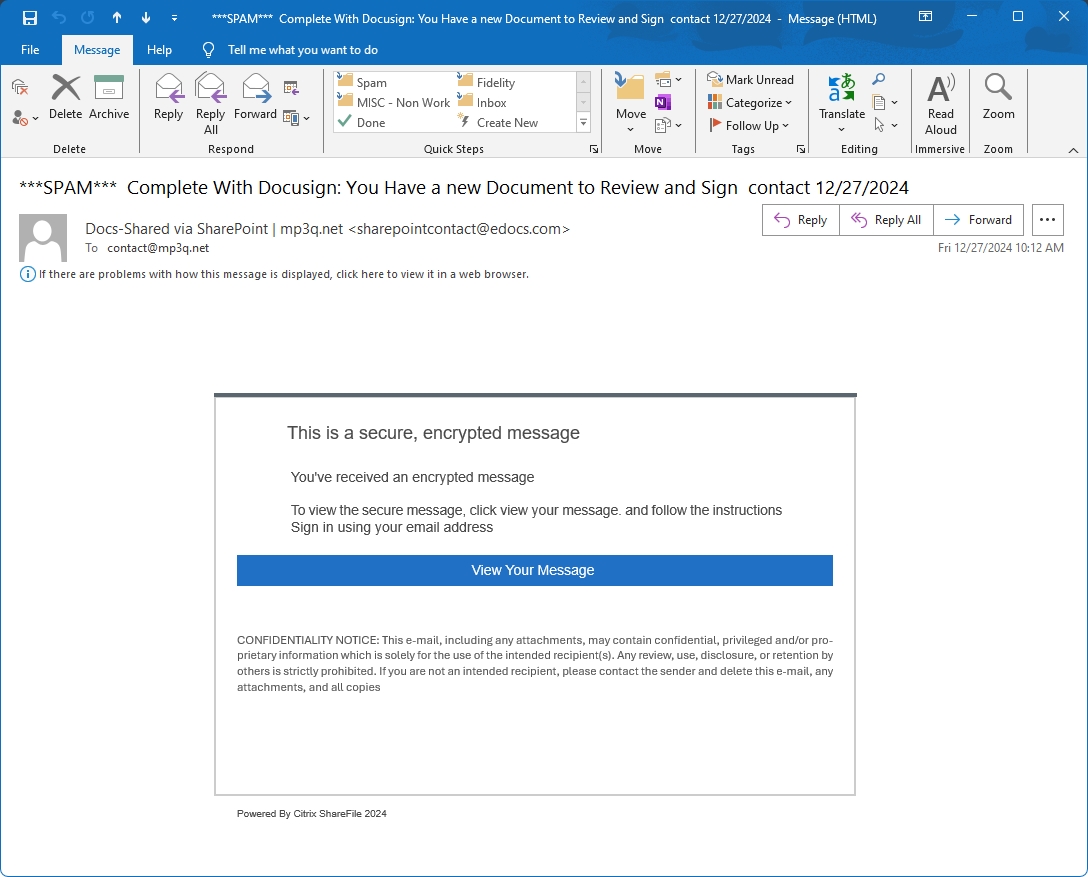

I was looking at my spam folder, and I noticed a DocuSign phishing email. It was also blending Microsoft Office elements. The lure (email) made a very poor attempt to pass itself off as legitimate.

Still, I decided to poke at it.

Looking at the message, the intent is clear. The threat actor who sent the email is trying to get me to click on the “View Your Message” link and open the phishing website.

The fake confidentiality notice is a decent touch, but if you examine this email, it just feels wrong. The blending of DocuSign and SharePoint elements, the awkward use of my email (which exists to catch scams like this), even the mention of a competing service at the footer of the message (Citrix isn’t related to DocuSign).

However, I collect phishing kits, which are the scripts and files needed to stage a phishing attack. I wanted to see if there was a new DocuSign kit on the other end of this scam.

Instead, I got something way more interesting.

Beware of the Blob

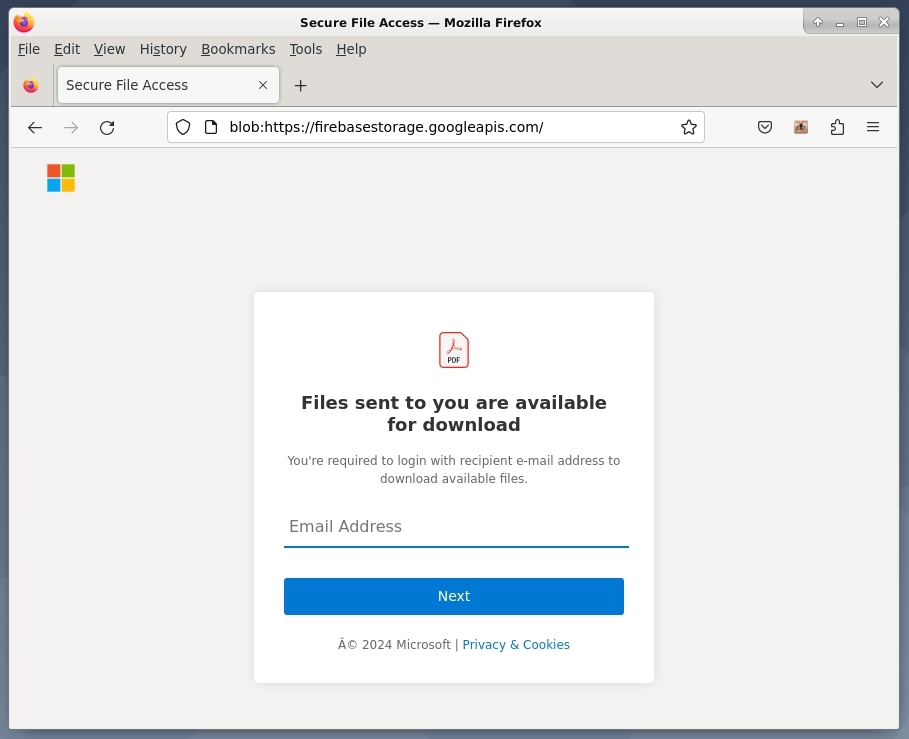

Once you click the link in the email and the threat actor’s page is loaded, it looks like any other Microsoft phishing scam. The intent is to get a victim’s username and password for office. If the victim happens to turn over enterprise credentials, then the threat actor responsible for this attack has hit the jackpot.

However, something is off.

The character mismatch in the footer, that is normal. Hosting the phishing page on Google’s Firebase? Again, pretty common these days.

In fact, Brandon Evans, of SANS, published an interesting paper on Firebase back in 2020 (hat tip: @ ISOM). In it, he concluded:

“…Firebase is unique in the degree to which their services are insecure by default and easy to misconfigure. Further, their flagship product has several inherent security concerns…”

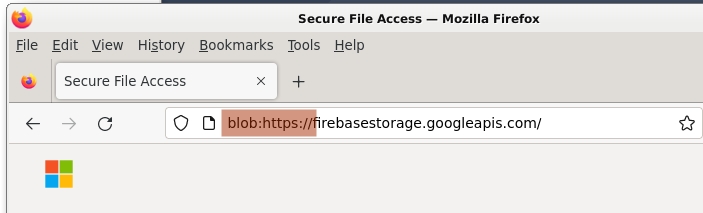

As for what’s off about the landing page I’m looking at, it’s the usage of “blob” in the address bar.

I know what blobs are, at least in the sense of object URLs.

The blob URI scheme is used to access local API-generated data. Binary Large OBjects (BLOB) are commonly used for images or downloads of binary data. But this was the first time I’ve encountered a blob-based phishing page.

I wanted the code (spoiler: I got the code.), because I needed to know how they’re doing this.

The why is easy. Using blobs like this helps the attacker remain undetected longer, because most scanning will miss blob-based rendering. Not all of it, but most.

Tracking the scam with URLScan

There is a tool, URLScan, which is used daily by defenders across the globe.

It can provide an amazing amount of intelligence about a given URL, without the worry of opening strange links on your local system. Honestly, if you’re not already using it, you should be. It’s how I was able to track this phishing campaign down to its base elements.

The original URL in the email was a t.co URL, which is the URL shortening service used on Twitter. Once expanded, the t.co URL forwarded to a Google Firebase domain, which is where the blob is rendered.

INDEX Inclusions

The INDEX file used for the phishing website calls out to external resources hosted on a .ro domain, which is either a compromised WordPress installation, or one that was created in order to host the JavaScript needed for this attack.

These external files are what hold the phishing page’s source code, as there is nothing really hosted on Firebase other than a simple INDEX file.

<script type="text/javascript"

src="hxxps://redacted/wp-includes/Requests/tmp1/jquery.js" >

</script>

<script type="text/javascript"

src="hxxps://redacted/wp-includes/Requests/tmp1/basic.js" >

</script>

URLScan came in clutch here, because I was able to see the external connections in the scan report and the related files.

The Blob

An examination of the JavaScript reveals the Base64 code needed to render the phishing page, which gives me my code.

$(document).ready(function() {

saveFile();

});

function saveFile (name, type, data) {

if (data != null && navigator.msSaveBlob)

return navigator.msSaveBlob(new Blob([data], { type: type }), name);

let a = $("<a style='display: none;'/>");

let encodedStringAtoB = 'Base64 code goes here';

let decodedStringAtoB = atob(encodedStringAtoB);

const myBlob = new Blob([decodedStringAtoB], {type: 'text/html'})

const url = window.URL.createObjectURL(myBlob);

a.attr("href", url);

$("body").append(a);

a[0].click();

window.URL.revokeObjectURL(url);

a.remove();

}

Code Acquired

Phishing attacks using blob-based rendering are going to become more common as criminals look to obfuscate their attacks.

However, the clear sign that something is wrong sits just before the HTTPS in the address bar. Anything asking for personal information or passwords that has an address starting with blob: should be viewed as malicious.

This is also another example where a password manager could help, as the auto-fill doesn’t activate on blob pages.

As for me, I had an excuse to write and I got new code for my phishing collection.

Turned out to be a good day.