An Office of Inspector General (OIG) report says that 21% of the US Department of the Interior (DOI) passwords were easily cracked during a recent test. The report found rampant password reuse, weak password schemes, and a lack of MFA.

Since I’ve been talking about passwords and the risks associated with them this week, I felt an overview of the report was in order.

Password Problems at the DOI

The title of the report says it all:

P@s$w0rds at the U.S. Department of the Interior: Easily Cracked Passwords, Lack of Multifactor Authentication, and Other Failures Put Critical DOI Systems at Risk

According to the report, the OIG spent about $15,000 USD to build the cracking rig used in the test.

The wordlists were comprised of the RockYou2021 list, which is a collection of words and known passwords that have been previously compromised and released to the public. In addition to RockYou2021, the report also references wordlists made up of dictionaries from multiple languages, U.S. Government terminology, and pop culture references. The OIG also used cracked DOI passwords to generate new wordlists.

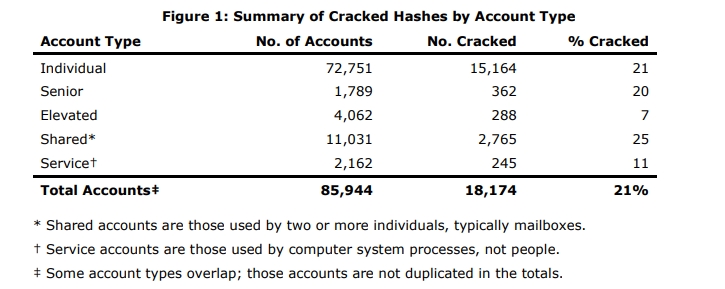

In all, the OIG was able to crack 21% of the DOI passwords, and 16% of those were cracked within the first 90 minutes of testing.

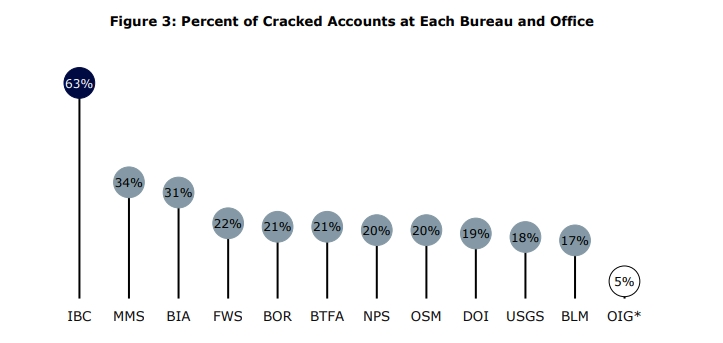

There were 14 agencies tested, including the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA); the Bureau of Land Management (BLM); the Bureau of Reclamation (BOR); the Bureau of Trust Funds Administration (BTFA); the Interior Business Center (IBC); the Minerals Management Service (MMS); the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM); the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE); the Office of Natural Resources Revenue (ONRR); the National Park Service (NPS); the Office of Inspector General (OIG); the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE); the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS); and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

The OIG report really centers on the need for MFA adoption, and urges DOI to speed up their efforts, citing the cracked passwords as a key risk.

In particular, in the first 90 minutes of testing, our hash-cracking system obtained clear text passwords for 13,924 (16 percent) of 85,944 Department Active Directory (AD) user accounts. Overall, we cracked 18,174 (21 percent) of the Department’s AD user accounts. We also cracked 288 passwords for accounts with elevated privileges and 362 passwords belonging to senior Government employees (GS–15 or higher, including senior executives)—among them, passwords belonging to 3 high-level OCIO management accounts and a total of 54 senior executives Departmentwide.

We also learned that the Department’s password complexity requirements implicitly allowed unrelated staff to use the same inherently weak passwords and that the Department did not timely disable inactive accounts or enforce password age limits. It is likely that if a well-resourced attacker were to capture Department AD password hashes, the attacker would have achieved a success rate similar to ours in cracking the hashes.

The OIG found a wide variance between bureau and office, as shown in the image below. This demonstrates that things are not equal between the agencies at DOI, and there is a clear disconnect between policies and processes.

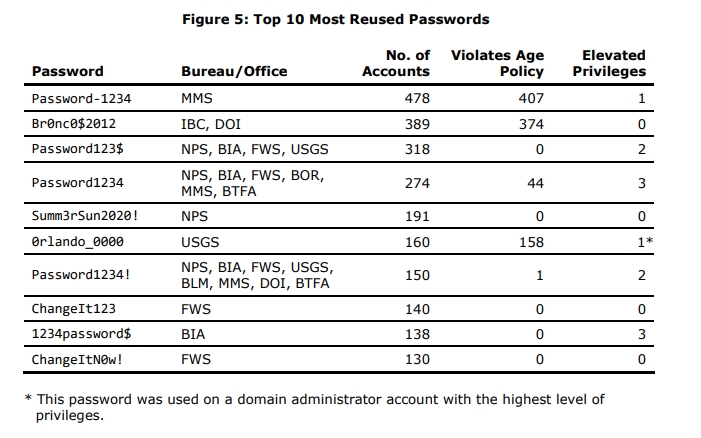

The types of passwords that were commonly reused across accounts (see image below) present a serious problem. Not only are they easily cracked and guessed, they belong to high-value assets. If these passwords were compromised, then the threat actor would have little problems leveraging the access granted to move about the network.

Government Data Breaches are Expensive

The risks highlighted by the OIG report are grounded in a reality that passwords alone are not enough when it comes to protecting critical assets, and that password policies need to be uniform, and equally enforced. On top of that, their premise is rooted in financial fact. A report from Comparitech (a pro-consumer website focused on security and privacy improvements) shows that data breaches by local, state, and federal government agencies have cost $26 billion USD over the last eight years.

Since 2014, the US government has suffered 822 breaches affecting nearly 175 million records. Based on the average cost per breached record (as reported by IBM each year), we estimate these breaches have cost government entities over $26 billion from 2014 to October 2022.

Now, one could argue that if the cost of a breach presented by IBM isn’t factual, then the results presented by Comparitech are skewed. I would argue that the IBM report, based on how the data is collected, is likely the closest thing the public will ever get to an actionable cost per-record accounting. So I fully believe in the IBM metrics and reporting. If you want to know how they arrive at their figures, each report has a methodology section, as well as FAQ, and a scope limitation section.

Bottom Line

The OIG report, matched with the Comparitech report, paints a problematic picture to be sure. However, the DOI is working to address these problems, and is on-track to meet their required protection measures. Many of the recommendations made by the OIG will be implemented by the DOI in the first half of 2023, and others will be implemented by 2024.

OIG Report Summarized

The Department did not consistently implement multifactor authentication, including for 89 percent of its High Value Assets (assets that could have serious impacts to the Department’s ability to conduct business if compromised), which left these systems vulnerable to password compromising attacks.

The Department’s password complexity requirements were outdated and ineffective, allowing users to select easy-to-crack passwords (e.g., Changeme$12345, Polar_bear65, Nationalparks2014!). We found, for example, that 4.75 percent of all active user account passwords were based on the word “password.” In the first 90 minutes of testing, we cracked the passwords for 16 percent of the Department’s user accounts.

The Department’s password complexity requirements implicitly allowed unrelated staff to use the same inherently weak passwords—meaning there was not a rule in place to prevent this practice. For example, the most commonly reused password (Password-1234) was used on 478 unique active accounts. In fact, 5 of the 10 most reused passwords at the Department included a variation of “password” combined with “1234”; this combination currently meets the Department’s requirements even though it is not difficult to crack.

The Department did not timely disable inactive (unused) accounts or enforce password age limits, which left more than 6,000 additional active accounts vulnerable to attack.